On Mon, Feb 4, 2013 at 11:51 PM, Steve Gadd wrote: “so you finish a marathon, and instead of sitting and resting and gloating, you … do a marathon: boggle”

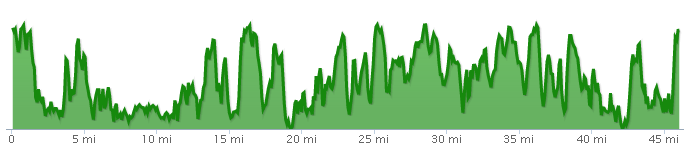

Thus did this wannabe grapple with the concept of a 50-mile trail race, the 2013 Bull Run Run. My first two official races were a local 5K in 2010 and the Marine Corps Marathon in 2011, so I don’t mind skipping over intermediate distances, but I had plenty of time to train up for my first marathon. The Bull Run Run was coming up in two months and would extend my maximum distance by over twenty miles, as well as adding an awful lot of hills. The organizers talk these hills down — “An elevation profile map would be a straight line with a lot of very little bumps” — as if a breath-stealing hike up a minor mountain is no big deal compared to the uncommonly long horizontal distance you are expected to cover.

I also had plenty of mental time to worry about the October marathon, since I had to commit far in advance during a frenzied registration in February, allowing plenty of time for research and a pretty regular training regimen, albeit on my lazy once-a-week schedule. The BRR, in contrast, is a model of fairness and sobriety, with no mad browser refreshing, no panic buying under a deadline. In fact it is a seductive trap, promising all manner of outs while you are still unsure of the whole concept. The initial signup is free, so there’s no good reason not to sign up. Then they hold a lottery to cut the number of runners down to 350, so you can let fate decide for you. Except there aren’t very many more than 350 applicants, so most everyone gets in. Then you have to pay, within some comfortable amount of days, or someone on the waitlist will take your spot. But even then it’s hard to make excuses, since you can transfer your registration later. It’s all very seductive, and suddenly the race is a week away, you haven’t been running for a month, and you realize you really want to at least start this thing, just to see what happens.

We got going at first light, right at 6:30. The first ten miles were just fine, easy and fun. Ray and I started near the back of the pack, with no complaints about the energy-conserving traffic jams. According to plan, we walked up anything with a positive grade from the start. There were lines for troublesome rocky passages and stream crossings, another excuse to break cadence for a minute or two.

Ray kept me company a while, then said something about “moving up a few positions” and that was the last time I saw him going the same direction. At the Reston ten-miler in March, I was too disciplined with maintaining my pace and did nothing to keep up when he pulled ahead. If I had pushed harder, I probably would have flamed out before the end, or been more hampered by blisters, but an hour now seems like a pretty short time to suffer for a cause. This time my conservative goal was to finish a marathon distance — barely more than half the course — so I was determined to observe the mantra “my race, my pace.”

My goals were, in increasing order of desirability:

- Cover 26.3 miles: Beat my distance record, in the hills. This seemed like an accomplishment, especially since I had run fewer than 50 miles total all year. I would have to find a place to declare myself a quitter, then make my way back to the start/finish, head hanging. My first DNF.

- Do the marathon distance and keep going until breakdown. Less convenient, more noble.

- Finish the course before the cutoff time of 13 hours. This seemed too unlikely an outcome to give much thought to.

The first aid station was at mile 7. Not needing my stopwatch to time the event (the time of day, or even the movement of the sun was accurate enough), I decided to use it to measure my stopped time at aid stations and other interruptions. I spent over four minutes at that first stop, walking in circles, confused, trying to figure out what to eat and what to do. I had already eaten a Clif bar and maybe a gel. I grabbed a cookie and a potato chip and drank some Gatorade, and used it to wash down my first S-Cap. Then I saw the sign indicating that we would be back after 4.5 miles and realized I was wasting time. I moved on.

Soon, the leader passed me going the other way. As usual on the trail, my brain was overwhelmed with thoughts of root-avoidance and it took me a second to realize that he was in my race and that the first turnaround was ahead. The expressions of the lead runners (certainly not jogger/walkers like me) were positively inspiring, showing hunger and drive and determination. I continued along the sometimes rocky, sometimes muddy trail, now watching ahead for oncoming traffic.

The first thought of quitting came during the eighth mile.

I hit the first turnaround after about two hours, 9.3 miles. Overall pace 12:38. I recalled prior estimation that a 15 minute/mile pace would get a runner to the finish on time with a bit of cushion, and I started performing the tedious, simple calculations that would tax my mind for most of the day. I also counted the people I saw behind me after the turn. By the time the crowds thinned there were about 70. A few stragglers and a few passes got me up into the mid-80s by the time I got back to the aid station. I restarted my stopwatch and added another two minutes to my stoppage time, refilled my bottle with water and remembered to dump the trash I had been carrying since before the first stop.

Ten miles in 2 hours 5 minutes; overall 12:30 pace.

mile / pace / elevation (ft)

1 / 11:54 / -39

2 / 13:37 / -101

3 / 12:19 / -14

4 / 12:48 / +27

5 / 13:37 / +74

6 / 11:52 / -55

7 / 11:56 / -51

8 / 13:53 / -11 (aid station)

9 / 11:57 / +17

10 / 11:34 / -2

The next ten miles were not painful, but I slowed down significantly, from 12.5 minutes/mile to 14.5. I was still on track to beat the cutoff, but didn’t know what to expect in the afternoon. The weather was perfect in the morning, comfortably chilly, but it was supposed to get up to 70. I felt a need to eliminate, but it wasn’t urgent and I didn’t want to lose time squatting in the woods, watching my stopwatch count up idle minutes. I started making plans for when I reached my drop bag at the start/finish area near mile 16. I ate a second Clif bar to make space and made a mental review of my inventory.

I started the race with

- my dirtier pair of sneakers

- Drymax lite trail running socks (an excellent recommendation)

- compression shorts

- bathing trunks (left front pocket for gels, right for trash)

- Nathan Triangle belt carrying water, two white chocolate macadamia nut Clif bars, three or four Gu gels, and two small zippered pockets transferred from another belt with Band-Aids, tissues, S-Caps, ibuprofen

- smartphone in armband with Runkeeper recording

- digital watch

- tech shirt

- hat

- sunblock cadged from Ray, mixed with borrowed bug spray, tasted awful

My drop bag contained

- spare shoes

- spare socks

- spare shirts

- spare belt

- headphones (prohibited during the early part of the course)

- Chia seeds (with some mixed in 8 ounces of water)

- Snickers bar

- Clif bars

- Pop-tarts

- assorted gels

- Body Glide anti-chafing stick

- athletic wrap

- Band-Aids

- tissues

- cell phone charger and cable

- flashlight

- paperback

It should have also contained

- water

- Gatorade

- lip balm

- sunblock

- towel

- wet wipes

I spent an unconscionable amount of time fussing with my drop bag despite careful planning. Before the race I had done my best by the instructions for the anti-chafing stuff: “APPLY WHERE NEEDED.” I had never needed it before and so rubbed it on places I imagined were likely to be annoyed by a day on the run. Now I added more around my waist where the belt was rubbing. My phone was still mostly charged, but I plugged in the backup charger and put it in my pocket, feeding the cable through my shirt. I was afraid I might be stranded somewhere remote come evening. I emptied and restuffed the belt pocket, rooting for more gels I felt sure I brought. I put the headphones in a pocket in case I needed inspiration later, but would never use them. I chugged the chia seed mix. I then walked the aid station, which was looking more like the sizable buffet later stations would have.

My estimated position was 92 from the back. In recent years roughly 30 starters failed to finish, so I felt like I was in a good spot. I was determinedly walking the rises with a hunched-over, knuckle-dragging Neanderthal plod, and usually returning to a regular trot at the top. I felt like I did pretty well on the climbs, where I executed a lot of my passes. Going up one hill, I noticed a novelty: I could hear my heartbeat. It made it easy to measure my pulse, 150 bpm. Safe enough, but I decided I wouldn’t start running while I could hear my heart pounding. Fortunately, after that climb I never heard it again. There were also some tricky descents which I also walked, telling myself I was avoiding a turned ankle but also glad of the excuse to take a break.

I chatted briefly with some other runners and eavesdropped on others, but usually didn’t keep pace with anyone long enough for much conversation. I tried to memorize bib numbers of interesting participants, but couldn’t keep them straight. There was a surprising amount of math involved in the endeavor. Simple arithmetic, but I couldn’t divide by 4 with my legs, where most of the oxygen was going. I calculated again and again my ETA based on a 15 minute per mile pace, never trusting the result. I maintained a count of the runners behind me. I kept track of the number of cumulative minutes I was ahead, and later behind, my target pace. Finally I focused on the number of minutes of cushion I estimated I had — how far ahead of the final cutoff I would be if I maintained 4 mph for the rest of the course.

Twenty miles in 4 hours 27 minutes; overall 13:21 pace.

mile / pace / elevation (ft)

11 / 11:58 / -10

12 / 13:13 / +39 (aid station)

13 / 12:01 / -20

14 / 14:26 / +121

15 / 12:12 / -130

16 / 13:23 / +128

17 / 23:41 / -26 (drop bag)

18 / 12:48 / -45

19 / 13:42 / -85

20 / 13:59 / +23

The next ten miles were a slog. It wasn’t even noon of this all-day affair, and I was just approaching the halfway point. I began extending my walking sessions. At the start of each mile, I noted the time and added fifteen minutes for a target time. Then at the end of the mile, I subtracted the overage minutes from my cushion. I had calculated that 50 miles at 4 mph would give me one hour of cushion, and didn’t want to depend on it too much. I got a little boost passing the 25 mile mark, and soon after passed the marathon distance and recognized that every step was a new personal record for distance. But it was still a slog. I passed the imaginary point where I had estimated that I could quit and walk back to the finish if necessary, but wasn’t aware of it. The leaders had passed the second turnaround and started coming from the other direction, still running, still looking determined, though hollowed out somehow. Some of them were running up hills faster than I was running down them. That’s why they’re called leaders, I reasoned.

I entered the White Loop around mile 27, a two-mile detour that is omitted on the return leg, so there was no oncoming traffic and very little company. No witnesses: I walked the whole thing. I continued doing the math every mile, but it seemed obvious I was eating into my cushion at a rate that would lead to disqualification. Gradually my attitude shifted, from worrying about getting back to the finish somehow before dark, to resolving that I would keep moving forward on the damn course until somebody made me stop.

There were more aid stations, some with cute themes. I hated that some of my miles took a minute or two over my target because I stopped for chow, but knew I couldn’t afford to skip them. I worked out a strategy for a disciplined, efficient pit stop.

- Run all the way into the aid station — you are about to take a break, you lazy slacker!

- Stop running, start the stopwatch.

- Hand off bottle for refill.

- Dispose of trash. I often forgot this step.

- Grab a PB&J sandwich quarter and a Gatorade cup, force them down.

- Recover and stow bottle.

- Refill or grab another cup, chomp some Pringles or cookies or something.

- Grab two sandwich quarters.

- Stop timer.

- Walk out, eating sandwich.

This technique got me through an aid station in one to two minutes, depending on the crowd and the help. The support was amazing on this race, both in positive attitude and eagerness to render assistance. And the food was plentiful. I subsisted mostly on the PB&J quarter sandwiches, or peanut-butter-and-Nutella when available. Later in the day the bread was sometimes dried out, but I found the Kobayashi tactic of soaking a mouthful in Gatorade made the whole thing go down easier, and was not even disgusting. (I have not tasted peanut butter, jelly or Gatorade since, however.)

One aid station had an amazing spread. In addition to the sandwiches and cookies and chips and fruit, and a bowl of bacon, a side table was loaded with a comprehensive array of equipment. Vaseline, Body Glide, Band-Aids, aerosol sunscreen, bug spray, S-Caps, painkillers, and duct tape. I reapplied sunblock, took another S-Cap, and was glad I didn’t need the duct tape. I was taking the electrolyte capsules something less than once an hour, not sure if I should be more concerned with an overdose or a shortage. In the second half of the course I started refilling my bottle with Gatorade instead of water, and backed off a bit on the pills.

I plodded on. It was time for the Do Loop.

Thirty miles in 7 hours 22 minutes; overall 14:44 pace.

mile / pace / elevation (ft)

21 / 21:12 / +66

22 / 15:29 / -16

23 / 15:41 / +74

24 / 15:52 / -91

25 / 18:58 / +80

26 / 14:58 / -75

27 / 21:40 / +63 (White Loop)

28 / 19:20 / +26 (White Loop)

29 / 17:10 / -11

30 / 15:13 / -52

Ray was kind enough to offer me a room the night before at his place nearby, and a coach to provide rides and encouraging hugs. In March, he had taken me on a tour of the Do Loop and the White Loop, about 12 miles total of the course, which he knows up and down. This was invaluable intel, and to my shame was my last training run before the race, over a month in advance. So I felt at least mentally prepared for the loop at the southeastern end of the course, the name of which seems always to follow the word “infamous.”

A popsicle from the last outbound aid station was a good way to get started, and I kept to my pattern of taking a mile at a time and walking all the rises and most of the descents, of which there were plenty. I passed the Nash Rambler, picking up the Bruce Springsteen tune it was blasting in an endless loop and carrying it with me for the next several miles.

Finishing the Do Loop it was quiet and lonely, another one-way section. The hills were considerable, but not so very much more challenging than others throughout the course. I continued, mostly walking, starting to regret that I wouldn’t be getting the finisher’s premiums. I caught up, while walking, to a competitor who was busy texting. It was his first 50 as well, and he complained a bit that the course map did not have an elevation profile. He seemed to want to chat, but he was going even slower than I felt like going, so I marched ahead. I jogged now and then, eventually pulling up to a couple of guys who kept a very disciplined pace. They walked rises, but always picked it up again at the top. I decided to keep them in sight. They pulled me through some tough miles, and I even got ahead of them briefly when they lingered at an aid station. But eventually they faded out of sight ahead when I couldn’t convince myself to give up walking on a long level stretch. I’ll just walk a little longer, then start running. Just a little longer.

Then, someone came up from behind. I hadn’t been passed by anyone for some time. He had a shirt with words on it and a weird blue bib. Something wasn’t right. Then it clicked — he was a sweeper! I sped up, but the sweeper wasn’t subtle at all and left little distance between us. This was going to be the end; I had burned up my cushion and they would stop me at the next road crossing or aid station. Then I looked at my bib; it was also blue. He was just another runner. But he had put the fear in me. I popped a couple ibuprofen tablets, though I wasn’t in agony. It helped considerably; soon I was able to maintain a measured running pace again.

The math still seemed to be against me. I had realized that a 15-minute mile pace would only leave a 30-minute cushion before hitting the 13-hour cutoff for the finish, and I was sure I had already used it up, and my average speed was only getting slower. I arrived at an aid station and saw the coach again — she had given me an encouraging pep talk when I passed by outbound. This time she congratulated me on having become an ultramarathon runner. I said — optimistically I thought — that we would see. No no, she said it was in the bag, I just had to cover a little more ground to get to the marina and I could “walk it in” from there. That sounded appealing, but I was full of doubt and confusion. Reluctantly, I waved goodbye and rejoined the trail.

I plodded on, calculating and recalculating. I had finished 36 miles, and had less than four hours before cutoff. With my recent pace of 16 to 20 (!) minutes per mile, I wasn’t going to make it. Then I saw the sign: 10 miles to Hemlock Overlook, the finish. I pulled out my phone for the first time and counted the mile markers on my outbound track. It seemed right, the end was in sight! I finished the ten-miler a month before in 1 hour 21 minutes. Now half that speed would be sufficient, and that’s about as fast as I could manage. I adopted a face-saving lope when I saw people fishing or hiking on the trail ahead. It’s just too ridiculous to walk level ground with a race bib, no matter how long you’ve been going. One guy told me it was just a mile to the marina ahead, where I would pass the final aid station and then five miles to the finish. I took one more ibuprofen tablet and at some point sucked down a caffeine-loaded gel.

Forty miles in 10 hours 16 minutes; overall 15:24 pace.

mile / pace / elevation (ft)

31 / 17:46 / -16 (Do Loop)

32 / 16:16 / +38 (Do Loop)

33 / 20:30 / -29 (Do Loop)

34 / 16:57 / +54

35 / 16:10 / -17

36 / 17:00 / +55

37 / 15:59 / -43

38 / 17:09 / -84

39 / 16:35 / +81

40 / 19:19 / -77

I arrived at the last aid station at 5:10 p.m., awkwardly jogging in and thanking a spectator, who was clapping and calling out encouragement despite the fact that I was the only entrant in sight. While stuffing my face with my last PB&J sandwiches, I saw the posted cutoff for this location was 6 p.m. I had 49 minutes to spare, and knew for the first time that I was going to finish.

The record shows that I celebrated with a two-mile walk, posting my slowest consecutive miles since the White Loop promenade. But somewhere around mile 43 something came over me, and I entered a mode I didn’t know I had. Maybe it was the caffeine, maybe the thought of getting the thing done. I stepped up to a respectable run and started feeling great. The trail was flying by, and even the rises were no problem. My breathing was perfectly tuned, one breath for every two strides. I started passing people, eventually catching up to the pair I had tailgated for so long. They stepped to one side and one said “Have at it!” I just said thanks as people yielded the way, worried they would soon see me on the side of the trail, wheezing.

I came up to the tricky, rocky section alongside the river and hopped and jumped along, afraid the spell would end if I slowed. The river cut east after mile 44 and I pulled up behind a tall runner who seemed determined not to be passed. I paced her for several minutes, my shadow directly under her feet. Eventually she started making pained gasping noises, like a tennis player late in a match, and finally stepped to the side. I kept on, posting my fastest mile since noon.

Finally I slowed down for a breather and to suck some Gatorade, and thought I heard shouting. Could it be the finish? I picked up my feet again and rounded a bend, leaving the river behind. Instead of the finish line, I met a brutal, soul-crushing hill, as high as any I had seen all day (in fact I had already climbed the same hill, going to the drop bag, but that was just mile 16). I grudgingly hiked up to the top and started a determined jog. I had realized that I was coming up on twelve hours, and thought I could try to finish this project in half a day with a last good push. I was going to say as much to a lady I passed, but she looked like she was already digging deep. The cheers were now clear up ahead, and I turned a last corner and saw the finish. The clock read 11:59! I whipped off my hat and began sprinting the last fifty yards, keeping it up for good form after realizing that I had misread the clock and had minutes to spare. I was then a confused, spent doofus in the finish area, barely able to shake the RD’s hand, collect my loot, including a delicious cup of ice water, and make use of the most welcome item of the day: a wet washcloth.

GPS time 11:56:53, pace 15:31. Official time 11:55:31, 246 out of 295 official finishers, 322 starters.

mile / pace / elevation (ft)

41 / 19:17 / -21

42 / 20:29 / -14

43 / 15:50 / +98

44 / 15:11 / -81

45 / 12:59 / -4

46 / 14:15 / +149

47 / 15:24 / +7

This event was great fun. I don’t usually prefer out-and-back routes, but it was fantastic seeing the other runners coming back on the same path, many of whom offered a “good job” or other encouraging words. And with no pressure to PR, just to survive and hopefully get in by dark, it was never miserable, never like miles 18-20 of a road marathon. It was really very little like running two marathons. The first 26 miles, taking over six hours, was more like a walk in the woods with some running mixed in.

Recovery was, surprisingly, no worse than after a marathon. Spending all day at the event meant that I slept through the flushed, logy feeling I get for several hours after finishing a long race. My heart rate was back to a normal 65 the next morning. Sunday night I found a small blister on one foot, at the edge of the mostly-healed big blister from the ten-miler. My nose and lips were raw from blowing and wiping snot about a hundred times and, well, being a mouth-breather for twelve hours. By Monday I was climbing stairs again, but only out of spite.

A great day, and a great timeexperience!

A fine tale; I feel like I was there.

My favorite parts are the part where I move up a few places, the part where you hallucinate the sweeper, and of course your phoenixlike recovery and finish.

Thanks for the drop bag magic.

great report — congrats on your first ultra, Steve! — ^z